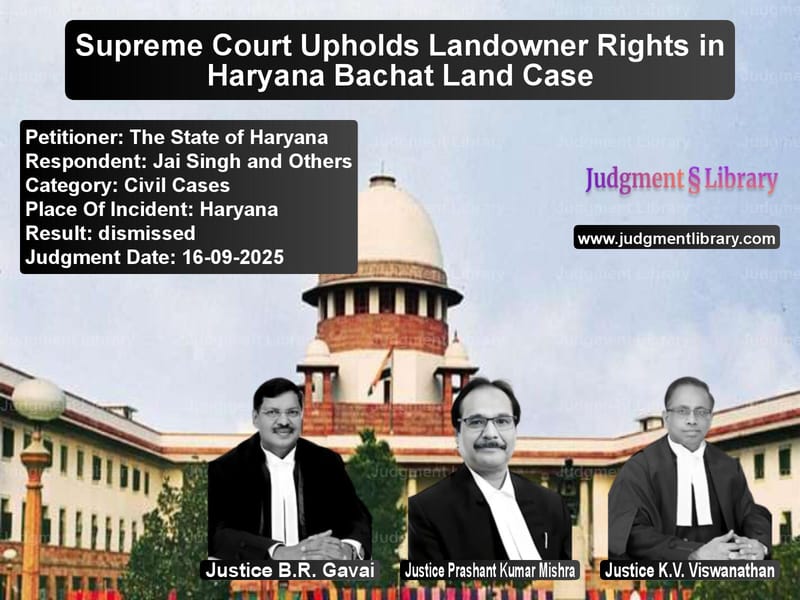

Supreme Court Upholds Landowner Rights in Haryana Bachat Land Case

In a significant ruling that affects thousands of landowners across Haryana, the Supreme Court has delivered a landmark judgment protecting the rights of farmers and landowners over what is known as ‘bachat land’ – surplus land left after consolidation proceedings that was never utilized for common purposes. The case, which has been winding through the courts for decades, centers around the fundamental question of whether the government can take over private land without compensation when that land was never actually used for the public purposes it was originally earmarked for.

The dispute dates back to 1992 when the State of Haryana inserted sub-clause (6) to Section 2(g) of the Punjab Village Common Lands (Regulation) Act, 1961 through Haryana Act No. 9 of 1992. This amendment expanded the definition of ‘shamilat deh’ (common village land) to include lands reserved for common purposes under the consolidation scheme, regardless of whether they were actually used for those purposes. The amendment essentially allowed the government to take control of bachat lands that had remained with the original landowners for decades after consolidation.

The landowners challenged this amendment before the Punjab and Haryana High Court, arguing that it amounted to compulsory acquisition without compensation. After a lengthy legal battle that saw the matter go up to the Supreme Court and back, the Full Bench of the High Court partly allowed the landowners’ petitions. The State of Haryana then appealed to the Supreme Court, leading to the current judgment.

The State’s Arguments

Shri Vinay Navare, learned Senior Counsel appearing for the State of Haryana, made several key arguments. He contended that ‘the lands contributed by the respondent-landowners on pro-rata basis during consolidation proceedings as carried out under the East Punjab Holdings (Consolidation And Prevention of Fragmentation) Act, 1948 would fall within the definition of ‘shamilat deh’ under the Haryana Act No. 9 of 1992. Such lands, he submitted, would vest in the State or Gram Panchayat, irrespective of whether they have been reserved for common purposes or not.’

Navare further argued that ‘vesting of such lands in the State or Gram Panchayat is complete as soon as the consolidation scheme attains finality and once so vested, the proprietors lose all rights and interests.’ He emphasized that the Haryana Act No. 9 of 1992 was merely clarificatory and did not divest proprietors of any ownership rights since those rights had already been extinguished under the consolidation proceedings.

Regarding the precedent set in Bhagat Ram’s case, Navare submitted that ‘this Court deliberately refrained from ordering the return of land to proprietors to avoid disrupting the consolidation scheme under the Consolidation Act of 1948. He submitted that returning bachat land to the proprietors would cause fragmentation and reverse the landholding structure to a pre-1948 scenario, which the Act expressly prohibits.’

The Landowners’ Counterarguments

Shri Manoj Swarup, learned Senior Counsel appearing for some of the landowners, presented a compelling case for the respondents. He argued that ‘the concerned land has been in their possession and under their cultivation from the very inception. As such, he submitted that, the respondent-landowners are the absolute owners of the land and they could not have been deprived of their proprietary rights without acquisition of the land through due process of law.’

Swarup contended that ‘the insertion of Clause 2(g)(6) with the Explanation in the 1961 Act, by way of the Haryana Act No. 9 of 1992, arbitrarily expanded the definition of ‘shamilat deh’. He submitted that the land of the respondent-landowners was neither reserved under the provisions of Section 18 of the Consolidation Act of 1948 for utilization for common purposes nor used for common purposes, but remained under their cultivation making them the absolute owners of the land.’

Shri Narender Hooda, another Senior Counsel for the landowners, emphasized the constitutional dimensions of the case. He submitted that ‘though the right to property is no more a fundamental right, it is still a constitutional right. It is submitted that in view of the law laid down by this Court in the cases of Ajit Singh v. State of Punjab and Another and Bhagat Ram, the land cannot be acquired where the beneficiary is the State.’

Hooda further drew attention to the practical realities, noting that ‘the Consolidation proceedings in the State of Haryana happened in and around 1960. It is submitted that, over the past 65 years, the possession of the bachat land remained undisturbed, despite earmarking, with the proprietors. He submitted that in some instances, the original proprietors remained in settled occupation. In many cases, bona fide transactions have taken place through registered sale deeds.’

The Court’s Analysis and Reasoning

The Supreme Court, in its judgment delivered by Chief Justice B.R. Gavai, conducted a thorough analysis of three crucial Constitution Bench judgments – Ranjit Singh, Ajit Singh, and Bhagat Ram. The Court noted that in Bhagat Ram’s case, the Constitution Bench had drawn a crucial distinction that became central to the current dispute.

Read also: https://judgmentlibrary.com/supreme-court-upholds-property-rights-in-land-dispute-case/

The Court reproduced the crucial reasoning from Bhagat Ram’s case: ‘We held in that case that there was this essential difference between ‘acquisition by the State’ on the one hand and ‘modification or extinguishment of rights’ on the other that in the first case the beneficiary is the State while in the latter case the beneficiary of the modification or the extinguishment is not the State. Here it seems to us that the beneficiary is the Panchayat which falls within the definition of the word ‘State’ under Article 12 of the Constitution.’

The Court further emphasized the critical holding from Bhagat Ram: ‘The income derived by the Panchayat is in no way different from its any other income. It is true that Section 2(bb) of the East Punjab Holdings (Consolidation and Prevention of Fragmentation) Act, 1948, defines ‘common purpose’ to include the following purposes: ‘… providing income for the Panchayat of the village concerned for the benefit of the village community.’ Therefore, the income can only be used for the benefit of the village community. But so is any other income of the Panchayat of a village to be used. The income is the income of the Panchayat and it would defeat the whole object of the second proviso if we were to give any other construction.’

The Court also noted the significant procedural requirement established in Bhagat Ram’s case: ‘It seems to us clear from these provisions that till possession has changed under Section 24, the management and control does not vest in the Panchayat under Section 23-A. Not only does the management and control not vest but the rights of the holders are not modified or extinguished till persons have changed possession and entered into the possession of the holdings allotted to them under the scheme.’

The Supreme Court agreed with the High Court’s distinction between lands actually reserved and used for common purposes versus bachat lands that were never utilized. The Court endorsed the High Court’s reasoning that ‘the lands which, however, might have been contributed by the proprietors on pro-rata basis, but have not been reserved or earmarked for common purposes in a scheme, known as Bachat land, it is equally true, would not vest either with the State or the Gram Panchayat and instead continue to be owned by the proprietors of the village in the same proportion in which they contribute the land owned by them.’

The Court also upheld the application of the doctrine of stare decisis, noting that ‘the doctrine of stare decisis lays importance on stability and predictability in the legal system and mandates that a view consistently upheld by courts over a long period must be followed, unless it is manifestly erroneous, unjust or mischievous.’ The Court referenced its own precedent in Maganlal Chhaganlal case: ‘A view which has been accepted for a long period of time should not be disturbed unless the Court can say positively that it was wrong or unreasonable or that it is productive of public hardship or inconvenience.’

The Final Ruling

In its concluding remarks, the Supreme Court firmly rejected the State’s appeal. The Court stated: ‘We have therefore no hesitation in holding that no error could be noticed in the impugned judgment and final order of the Full Bench of the High Court to the extent that it holds that the lands which have not been earmarked for any specific purpose do not vest in the Gram Panchayat or the State.’

The Court dismissed the State’s appeal, thereby upholding the rights of landowners over bachat lands that were never actually utilized for common purposes. This judgment reinforces the principle that the state cannot arbitrarily take over private property without due process and compensation, even when such property was theoretically earmarked for public use decades ago but never actually used for that purpose.

The ruling represents a significant victory for property rights in India and provides clarity on the limits of state power in land acquisition matters, particularly in cases where historical land consolidation proceedings have left ambiguous ownership situations that span generations.

Petitioner Name: The State of Haryana.Respondent Name: Jai Singh and Others.Judgment By: Justice B.R. Gavai, Justice Prashant Kumar Mishra, Justice K.V. Viswanathan.Place Of Incident: Haryana.Judgment Date: 16-09-2025.Result: dismissed.

Don’t miss out on the full details! Download the complete judgment in PDF format below and gain valuable insights instantly!

Download Judgment: the-state-of-haryana-vs-jai-singh-and-others-supreme-court-of-india-judgment-dated-16-09-2025.pdf

Directly Download Judgment: Directly download this Judgment

See all petitions in Property Disputes

See all petitions in Compensation Disputes

See all petitions in Judgment by B R Gavai

See all petitions in Judgment by Prashant Kumar Mishra

See all petitions in Judgment by K.V. Viswanathan

See all petitions in dismissed

See all petitions in supreme court of India judgments September 2025

See all petitions in 2025 judgments

See all posts in Civil Cases Category

See all allowed petitions in Civil Cases Category

See all Dismissed petitions in Civil Cases Category

See all partially allowed petitions in Civil Cases Category