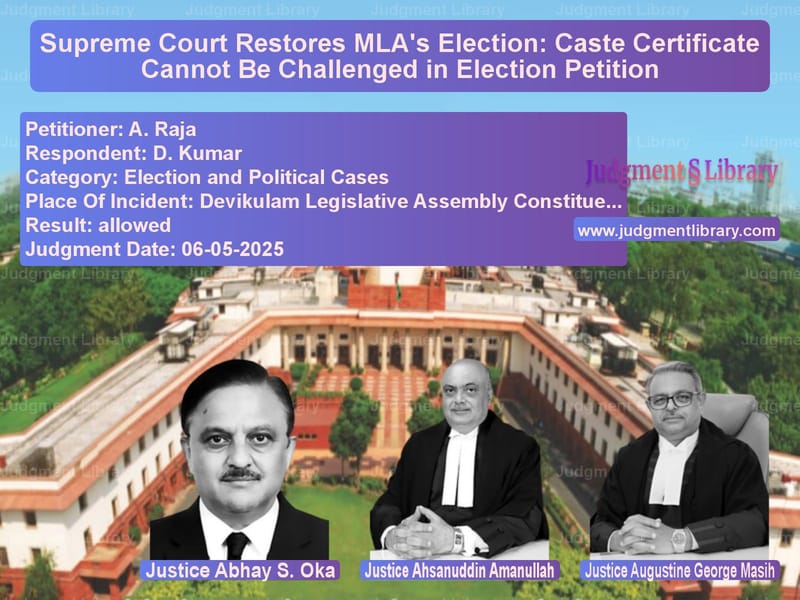

Supreme Court Restores MLA’s Election: Caste Certificate Cannot Be Challenged in Election Petition

In a landmark judgment that has significant implications for electoral law and caste certification processes in India, the Supreme Court restored the membership of A. Raja, a legislator from Kerala, setting aside the Kerala High Court’s decision that had declared his election void. The case, which revolved around the appellant’s caste status and religious identity, delved deep into constitutional provisions, evidentiary standards in election petitions, and the jurisdictional boundaries between different legal forums.

The legal battle began when D. Kumar, the defeated candidate in the 2021 elections for the Devikulam Legislative Assembly Constituency in Idukki District, challenged Raja’s election through an election petition. The constituency was reserved for Scheduled Castes, and Kumar contended that Raja did not legitimately belong to the Hindu Parayan caste in Kerala and was instead a Christian, thus making him ineligible to contest from a reserved seat.

The Factual Background

General elections to the Devikulam Assembly Constituency were conducted in 2021. Raja filed his nomination papers on March 17, 2021, declaring that he belonged to the Hindu Parayan caste based on a caste certificate issued by the Tehsildar of Devikulam. The Parayan caste is recognized as a Scheduled Caste in Kerala under the Constitution (Scheduled Castes) Order, 1950.

Kumar raised oral objections before the Returning Officer, claiming that Raja was not a member of Scheduled Castes from Kerala but was actually a Christian. The Returning Officer examined the nomination papers and rejected these objections, accepting Raja’s nomination. The election proceeded on April 6, 2021, and results declared on May 2, 2021, showed Raja winning with 59,049 votes, defeating Kumar by a margin of 7,848 votes.

Kumar then filed Election Petition No. 11 of 2021 before the Kerala High Court, arguing that Raja’s paternal grandparents had migrated from Tamil Nadu to Kerala in 1951. While ‘Parayan’ is included in the list of Scheduled Castes in both states, Kumar contended that since Raja’s grandparents migrated from Tamil Nadu, they and their successors could not claim to belong to the ‘Hindu Parayan’ community of Kerala. He further asserted that Raja’s parents had converted to Christianity in 1982 and that Raja himself was baptized, making him ineligible to contest from a constituency reserved for Scheduled Castes.

The High Court’s Decision

The High Court framed four issues for determination: whether Raja belonged to the Scheduled Caste among Hindus in Kerala; whether the acceptance of his nomination was proper; whether his election was liable to be set aside; and what relief and costs should be awarded. After examining witnesses and documents, the High Court declared Raja’s election void under Section 100(1)(a) and (d)(i) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951.

The High Court held that Raja’s grandparents were not permanent residents of Kerala before the 1950 Presidential Order and that Raja had converted to Christianity, thus losing his Scheduled Caste status. This decision led Raja to appeal to the Supreme Court under Section 116-A of the Representation of the People Act.

Arguments Before the Supreme Court

Senior counsel Mr. V. Giri, representing appellant Raja, made several crucial arguments. He contended that the burden to prove that Raja’s family had migrated to Travancore only after 1950 was entirely upon the election petitioner, relying on M. Chandra v M. Thangamuthu, where the Court held that the burden of proof is on the election petitioner to prove the charges beyond reasonable doubt.

Giri argued that the High Court had created a new case not pleaded by the respondent when it held that even though Raja’s ancestors started residing in Travancore before 1950, their residence was only for employment purposes and they could not be treated as permanent residents. This finding was assailed on the ground that it was neither pleaded nor proved by Kumar.

Regarding the caste certificate, Giri contended that there was no challenge to its validity. He emphasized that “the validity of the issuance of the community certificate is presumed unless shown otherwise by Respondent 1, who clearly failed to do so” as established in M. Chandra. Kumar had not examined either the Competent Authority that issued the caste certificate or the Returning Officer to prove any malpractice.

On the religious conversion aspect, Giri pointed to serious inconsistencies in the respondent’s evidence. The key witness, Ebenezer Mani (PW8), who claimed to have baptized Raja’s parents in 1982, admitted during evidence that he was only 14 years old in 1982, making his claim unbelievable. Furthermore, Giri argued that entries in baptism registers were not properly proved, contained overwritings and corrections, and showed dates of birth that did not match the actual dates of birth of Raja’s family members.

Read also: https://judgmentlibrary.com/supreme-court-reinstates-sarpanch-wrongfully-removed-by-bureaucracy/

Giri also stressed that the specific case pleaded in the election petition was that Raja’s ancestors migrated to Kerala in 1951, with no mention that they came for employment. He argued that after the period of limitation, a new contention changing the whole nature of the case could neither be raised nor pressed into service, relying on Goka Ramalingam v Boddu Abraham.

Senior counsel Mr. Narender Hooda, representing respondent Kumar, countered these arguments. He submitted that the burden of proving the authenticity of the caste certificate was fully on Raja under Section 10 of the Kerala (Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes) Regulation of Issue of Community Certificates Act, 1996, which states that “the burden of proving that he belongs to such Caste or Tribe shall be on the claimant” in any trial under the Act.

Hooda argued that an election petition would fall within the ambit of “any trial” contemplated under Section 10 of the Kerala Act. He relied on Hari Shanker Jain v Sonia Gandhi and Punit Rai v Dinesh Chaudhary to contend that a caste certificate issued to a returned candidate can be challenged in an election petition.

Hooda further submitted that a person claiming Scheduled Caste status in a particular state must demonstrate his or his ancestors’ permanent residence in that state on the date of the Presidential Order. Citing Action Committee on Issue of Caste Certificate to SCs/STs v Union of India, he argued that the word “resident” in the 1950 Order means “permanent resident.” The High Court had recorded a categorical finding of fact that Raja’s grandfather was not a permanent resident of Kerala before the 1950 Order.

On the religious conversion aspect, Hooda contended that when Raja’s parents converted to Christianity, the minor Raja had no right to claim any religion or caste different from his parents. He relied on K. P. Manu v Scrutiny Committee for Verification of Community Certificate to argue that the doctrine of eclipse followed Raja until he became a major, and it was his responsibility to prove that he had come out of this eclipse by reconverting to Hinduism.

The Supreme Court’s Analysis and Reasoning

The Supreme Court, comprising Justices Abhay S. Oka, Ahsanuddin Amanullah, and Augustine George Masih, began its analysis by examining Article 341 of the Constitution, which empowers the President to specify Scheduled Castes in relation to each state. The Court identified the twin conditions that needed to be satisfied for Raja to claim benefits as a Hindu Parayan in Kerala: (i) being of the Hindu Parayan caste, and (ii) being, himself or through his ancestors, a permanent resident of Kerala as on the date of the 1950 Order.

The Court noted that there was no dispute that Raja’s grandparents originally belonged to the Hindu Parayan caste and had migrated from Tamil Nadu to the erstwhile State of Travancore-Cochin prior to 1950. The crucial question was whether Raja had retained the Hindu Parayan caste as a member of the Hindu religion when he contested the election.

On the standard of proof in election petitions, the Court emphasized that “Election Petitions, including those wherein no allegations of corrupt practices are levelled, have to be treated akin to criminal proceedings and the Election Petitioner has to prove the charges levelled beyond reasonable doubt.” This principle, established in J. Chandrasekhara Rao v V. Jagapathi Rao and M. Chandra, guided the Court’s decision-making.

The Court found the evidence regarding religious conversion seriously lacking. Most importantly, Ebenezer Mani (PW8), who claimed to have baptized Raja’s parents in 1982, admitted during evidence that he was only 14 years old at that time. The Court found this “clearly, unbelievable and unsustainable.” Additionally, entries in baptism registers were not specific, contained overwritings and corrections, and showed names and dates that did not match Raja’s family details.

The Court made significant observations on what constitutes “professing” a religion, citing Punjabrao v D. P. Meshram: “The word ‘profess’ in the Presidential Order appears to have been used in the sense of an open declaration or practice by a person of the Hindu (or the Sikh) religion. Where, therefore, a person says, on the contrary, that he has ceased to be a Hindu he cannot derive any benefit from that Order.”

The Court further noted that “mere observance/performance of a ritual of/associated with any religion does not ipso facto and necessarily mean that the person ‘professes’ that religion.” Quoting from Sapna Jacob v State of Kerala, the Court observed: “a court can find the true intention of men lying behind their acts and can certainly find from the circumstances of a case whether a pretended conversion was really a means to some further end.”

On the crucial issue of whether a caste certificate can be challenged in an election petition, the Court conducted an extensive analysis of the Kerala Act and relevant precedents. The Court rejected the respondent’s contention that “in any trial” under Section 10 of the Kerala Act would include an election petition. Applying principles of statutory interpretation like noscitur a sociis and ejusdem generis, the Court held that “‘in any trial’ would refer only to a trial under the Act.”

The Court emphasized that the Kerala Act is a complete code in itself, providing an elaborate scheme for the issuance, verification, and cancellation of caste certificates. Special Courts are established under Section 21 to try offences under the Act, and Section 24 bars the jurisdiction of civil courts. Therefore, “a Caste/Community Certificate cannot be assailed in an Election Petition.”

The Court distinguished Sobha Hymavathi Devi v Setti Gangadhara Swamy, where it was observed that a community certificate could be challenged in an election petition, holding that this observation was made sub-silentio (without full consideration) and thus had no precedential value.

The Court also distinguished Hari Shanker Jain v Sonia Gandhi, which permitted examination of citizenship in election petitions, noting that there is a fundamental difference between a certificate of registration under the Citizenship Act and a community certificate issued under the Kerala Act. The latter involves a detailed inquiry process by the Competent Authority, which functions akin to a quasi-judicial authority with powers of a civil court.

The Court reiterated the principles from M. Chandra that “an election petition must clearly and unambiguously set out all the material facts which the petitioner is to rely upon during the trial” and that “the burden of proof is on the election petitioner to prove the charges he has made beyond reasonable doubt.”

The Supreme Court’s Conclusion

After comprehensive analysis, the Supreme Court allowed the appeal and set aside the High Court’s judgment. The Election Petition was dismissed, and Raja was entitled to all consequential benefits as a Member of the Legislative Assembly for the entire period from the date of his oath.

The Court clarified that it had not opined on the legality or otherwise of Raja’s caste certificate, stating that “Our view herein is not determinative of its validity or invalidity. Any challenge thereto, if and when raised in accordance with law, shall be considered on its own merits.”

The Court laid down an important principle that “a duly issued Caste/Community Certificate would be amenable to challenge only under the provisions of the statute concerned, and not in an Election Petition.” In states without specific legislation, the guidelines from Madhuri Patil v Commr., Tribal Development, as modified in Dayaram v Sudhir Batham, would apply.

This judgment significantly clarifies the jurisdictional boundaries between election courts and specialized mechanisms for caste certificate verification. It reinforces the high standard of proof required in election petitions and protects the validity of duly issued caste certificates from collateral challenges in election disputes. The decision underscores the importance of following established statutory procedures for challenging official documents rather than attempting to invalidate them through election petitions.

Petitioner Name: A. Raja.Respondent Name: D. Kumar.Judgment By: Justice Abhay S. Oka, Justice Ahsanuddin Amanullah, Justice Augustine George Masih.Place Of Incident: Devikulam Legislative Assembly Constituency, Idukki District, Kerala.Judgment Date: 06-05-2025.Result: allowed.

Don’t miss out on the full details! Download the complete judgment in PDF format below and gain valuable insights instantly!

Download Judgment: a.-raja-vs-d.-kumar-supreme-court-of-india-judgment-dated-06-05-2025.pdf

Directly Download Judgment: Directly download this Judgment

See all petitions in Reservation Cases

See all petitions in Constitution Interpretation

See all petitions in Fundamental Rights

See all petitions in Legal Malpractice

See all petitions in Other Cases

See all petitions in Judgment by Abhay S. Oka

See all petitions in Judgment by Ahsanuddin Amanullah

See all petitions in Judgment by Augustine George Masih

See all petitions in allowed

See all petitions in supreme court of India judgments May 2025

See all petitions in 2025 judgments

See all posts in Election and Political Cases Category

See all allowed petitions in Election and Political Cases Category

See all Dismissed petitions in Election and Political Cases Category

See all partially allowed petitions in Election and Political Cases Category