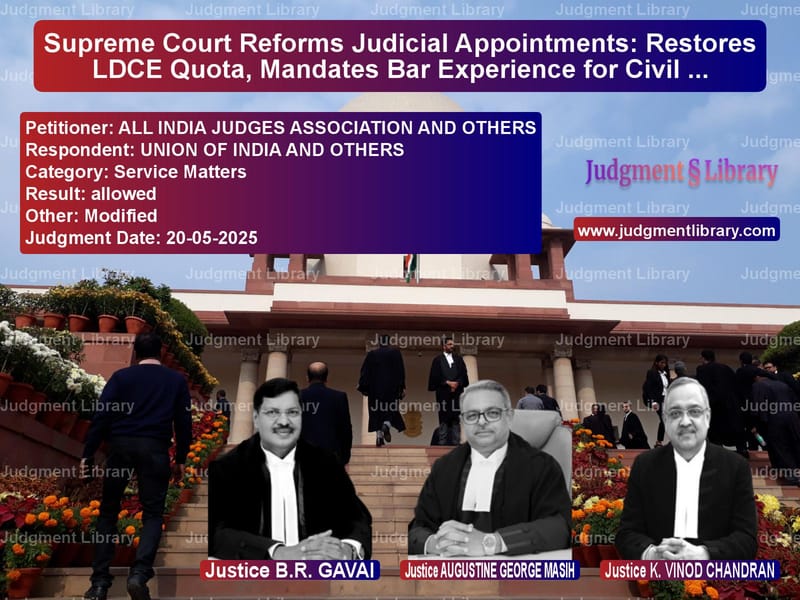

Supreme Court Reforms Judicial Appointments: Restores LDCE Quota, Mandates Bar Experience for Civil Judges

In a landmark judgment that promises to reshape the career progression and entry criteria for India’s judicial officers, the Supreme Court has issued a series of sweeping directives. The case, originating from a writ petition filed decades ago by the All India Judges Association, culminated in a detailed ruling addressing eight critical issues concerning the qualification, promotion, and selection within the subordinate judiciary.

The bench, led by Chief Justice B.R. Gavai along with Justices Augustine George Masih and K. Vinod Chandran, delved into the practical difficulties and administrative challenges that have emerged since its previous orders. The Court noted that its earlier decisions, aimed at strengthening the judiciary, required a fresh look based on the experiences of the last twenty years. The judgment meticulously balances the need for incentivizing merit with the practical realities of filling vacancies and ensuring a robust judicial administration.

Restoring the LDCE Quota for District Judge Promotions

A central issue before the Court was whether to restore the 25% quota for promotion to the Higher Judicial Service (District Judge cadre) through Limited Departmental Competitive Examination (LDCE), which was reduced to 10% in 2010. The Court traced the history of this provision back to the Shetty Commission recommendations and its own 2002 judgment, which had initially introduced the 25% quota to create an incentive for meritorious officers.

The Court observed that the original intent was to provide an opportunity for accelerated promotion. However, in 2010, due to difficulties in filling the 25% quota, it was reduced to 10%. Now, considering the changed circumstances and the availability of a sufficient number of eligible officers, the Court decided to restore the original quota. The Court argued, “if the quota of LDCE is restored to 25% as originally recommended… it will provide an incentive amongst the officers in the Cadre of Civil Judge (Senior Division). It will also provide them with an opportunity to get accelerated promotion… if they are meritorious and deserving.” To prevent vacancies, the Court directed that any unfilled LDCE posts in a particular year should revert to the regular promotion quota and be filled in the same year.

Reducing the Eligibility Experience for LDCE

Closely linked to the first issue was the requirement of five years of service as a Civil Judge (Senior Division) to be eligible for the LDCE. The Court found this requirement to be counterproductive. In many states, officers were becoming eligible for regular promotion around the same time they became eligible for the LDCE, thereby nullifying the ‘accelerated’ aspect of the promotion.

The Court noted a particularly anomalous situation in Gujarat, where for regular promotion, only two years of service was required, but for the LDCE, which is meant for faster promotion, five years were required. The Court found this “totally inconsistent with the idea of providing an incentive.” After reviewing data from various states, the Court reduced the minimum qualifying service for LDCE to three years as a Civil Judge (Senior Division), with a cumulative service of seven years including time spent as a Civil Judge (Junior Division).

Introducing LDCE for Promotion to Civil Judge (Senior Division)

In a significant move to incentivize merit at the lower rungs of the judiciary, the Court directed the creation of a new promotion channel. It mandated that 10% of the posts in the cadre of Civil Judge (Senior Division) be reserved for promotion of Civil Judge (Junior Division) officers through an LDCE mechanism. The minimum qualifying service for appearing in this examination was set at three years as a Civil Judge (Junior Division). The Court reasoned that the same principle of rewarding merit that applied to promotions to the District Judge cadre should also apply at this level.

Calculating Quotas on Cadre Strength

To ensure uniformity across all states, the Court directed that the quota reserved for LDCE must be calculated on the basis of the total cadre strength of the relevant post, and not on the number of vacancies arising in a particular recruitment year. This direction aims to bring consistency to the recruitment process nationwide.

Mandating a Suitability Test for Regular Promotions

The Court reaffirmed the necessity of an objective method to test the suitability of officers being considered for promotion to the Higher Judicial Service under the 65% merit-cum-seniority quota. It emphasized that High Courts must frame rules to assess candidates based on factors such as updated knowledge of law, quality of judgments, Annual Confidential Reports (ACRs), disposal rates, performance in viva voce, and communication skills. The Court recalled its earlier observation that “there should be an objective method of testing the suitability of the subordinate judicial officers for promotion to the Higher Judicial Service.”

Restoring the Bar Experience Requirement for Civil Judge (Junior Division)

Perhaps the most debated issue was the restoration of the requirement for a minimum period of practice at the Bar for candidates appearing for the Civil Judge (Junior Division) examination. This requirement was done away with in 2002 to attract fresh law graduates. However, based on affidavits from nearly all High Courts, the Court found that this experiment had not been successful.

The Court noted widespread complaints that officers appointed directly from college often lacked practical knowledge, faced difficulties in handling court proceedings, and sometimes exhibited behavioural issues towards bar members and staff. The High Court of Andhra Pradesh reported that such officers “are not treating the bar members and staff members in good spirits.” The High Court of Madhya Pradesh stated that “fresh law graduates having no experience at the Bar lack maturity and experience in handling court proceedings.”

Agreeing with these views, the Court held, “Neither knowledge derived from books nor pre-service training can be an adequate substitute for the first-hand experience of the working of the court-system and the administration of justice.” It, therefore, directed that henceforth, candidates must have a minimum of three years of practice to be eligible for the Civil Judge (Junior Division) exam.

Calculating Practice and Safeguards

Addressing concerns about how to calculate this practice period, the Court ruled that it should be counted from the date of provisional enrollment with a State Bar Council, not from the date of passing the All India Bar Examination (AIBE). To ensure that the requirement translates into actual practice and not just enrollment, the Court mandated that candidates produce a certificate from a Principal Judicial Officer or a senior advocate (with at least 10 years of standing) certifying their actual practice. Experience gained as a Law Clerk to a judge will also be counted towards this requirement. Furthermore, selected candidates must undergo at least one year of training before presiding over a court.

In its concluding directions, the Court gave all High Courts and State Governments a period of three months each to carry out the necessary amendments to their service rules. This comprehensive judgment marks a significant step towards creating a more experienced, efficient, and meritorious subordinate judiciary, strengthening the very foundation of the Indian judicial system.

Petitioner Name: ALL INDIA JUDGES ASSOCIATION AND OTHERS.Respondent Name: UNION OF INDIA AND OTHERS.Judgment By: Justice B.R. GAVAI, Justice AUGUSTINE GEORGE MASIH, Justice K. VINOD CHANDRAN.Judgment Date: 20-05-2025.Result: allowed.

Don’t miss out on the full details! Download the complete judgment in PDF format below and gain valuable insights instantly!

Download Judgment: all-india-judges-ass-vs-union-of-india-and-o-supreme-court-of-india-judgment-dated-20-05-2025.pdf

Directly Download Judgment: Directly download this Judgment

See all petitions in Promotion Cases

See all petitions in Recruitment Policies

See all petitions in Employment Disputes

See all petitions in Public Sector Employees

See all petitions in Judgment by B R Gavai

See all petitions in Judgment by Augustine George Masih

See all petitions in Judgment by K. Vinod Chandran

See all petitions in allowed

See all petitions in Modified

See all petitions in supreme court of India judgments May 2025

See all petitions in 2025 judgments

See all posts in Service Matters Category

See all allowed petitions in Service Matters Category

See all Dismissed petitions in Service Matters Category

See all partially allowed petitions in Service Matters Category