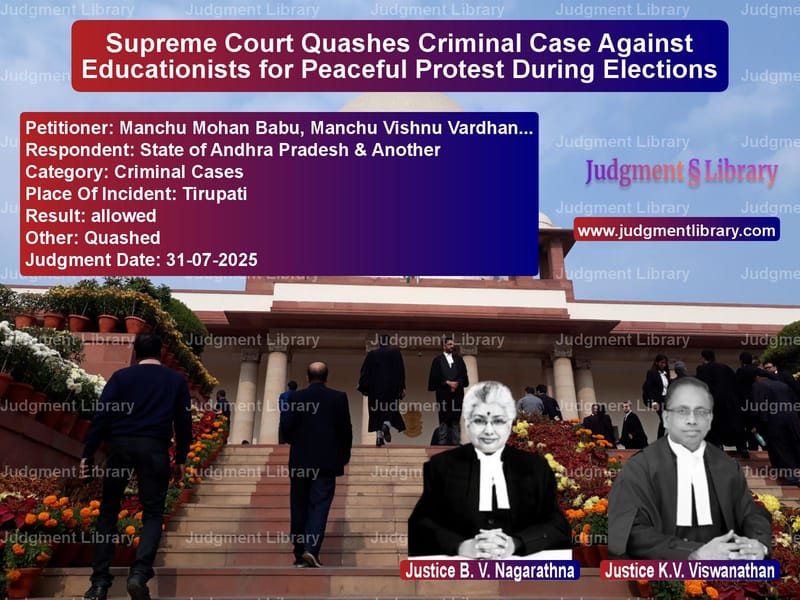

Supreme Court Quashes Criminal Case Against Educationists for Peaceful Protest During Elections

In a significant judgment that reinforces the constitutional protection of fundamental rights during electoral periods, the Supreme Court of India delivered a landmark verdict on July 31, 2025, quashing criminal proceedings against two educationists who had organized a peaceful protest during the 2019 general elections. The case involving Manch Mohan Babu, Chairman of Sri Vidyaniketan Educational Institutions, and his son Manch Vishnu Vardhan Babu, highlights the delicate balance between maintaining electoral discipline and protecting citizens’ rights to peaceful assembly and free speech.

The legal battle originated from events that unfolded on March 22, 2019, during the Lok Sabha and Legislative Assembly elections in Andhra Pradesh. The Model Code of Conduct had come into force on March 10, 2019, restricting public meetings, rallies, and demonstrations without prior permission from competent authorities. On March 13, 2019, the Sub Divisional Police Officer of Tirupati West had issued prohibitory orders under Section 30 of the Police Act, 1861, further restricting public gatherings.

According to the prosecution’s case, the appellants, along with staff and students from their educational institution, congregated at approximately 8:30 AM on March 22, 2019, to conduct a rally along the Tirupati-Madanapalli Road. The participants were described as raising slogans against the then-state government for not granting student fee reimbursements and conducting a dharna from 8:30 AM to 12:30 PM. The authorities alleged that these acts caused obstruction to traffic flow, inconvenience, annoyance, and risk to passengers.

The Mandal Parishad Development Officer, who was in charge of the Model Code of Conduct Team-IV for Chandragiri Assembly Constituency, arrived at the spot, videographed the rally and dharna, and registered a written complaint with the police. This led to the registration of FIR No. 102 of 2019 at Chandragiri Police Station against the appellants and other participants. After recording witness statements, a chargesheet was filed on June 3, 2020, against the appellants in C.C. No. 1015/2021 for offences under Sections 290, 341, and 171F read with Section 34 of the Indian Penal Code, and Section 34 of the Police Act, 1861.

The appellants approached the Andhra Pradesh High Court seeking quashing of the criminal proceedings, but their petition was dismissed on January 2, 2025, prompting their appeal to the Supreme Court.

Before the Supreme Court, senior counsel Sri Raghavendra S. Srivatsa, representing the appellants, made several compelling arguments. He contended that “the appellants were merely exercising their fundamental rights of freedom of speech and expression and that the rally and dharna in question did not cause any form of obstruction to the general public. That the rally and dharna were both conducted peaceably and without arms.” He further argued that “the Model Code of Conduct would not govern the appellants as they are private citizens. That the criminal proceedings initiated are nothing but an abuse of the process of law to scuttle the constitutionally guaranteed fundamental rights of the appellants.”

The appellants’ counsel also submitted that “the High Court has not appropriately applied the ‘Bhajan Lal test’ to determine if the criminal proceedings are to be quashed. That no ingredients of the alleged offences have been made out.”

Opposing these arguments, Ms. Prerna Singh, learned counsel for the respondent-state, contended that “the dharna and rally were conducted without prior permission of the concerned authorities, blocked the traffic for several hours and caused public nuisance and inconvenience. That reasonable restrictions may be applied to the fundamental right to congregate peaceably.”

The Supreme Court, in its analysis, began by examining the established legal principles for quashing criminal proceedings. The Court referenced the landmark case of State of Haryana vs. Bhajan Lal, which laid down parameters for exercising powers under Section 482 of the Criminal Procedure Code. The Court noted that “quashing may be appropriate in the following circumstances: ‘102. (1) Where the allegations made in the first information report or the complaint, even if they are taken at their face value and accepted in their entirety do not prima facie constitute any offence or make out a case against the accused. (2) Where the allegations in the first information report and other materials, if any, accompanying the FIR do not disclose a cognizable offence, justifying an investigation by police officers under Section 156(1) of the Code except under an order of a Magistrate within the purview of Section 155(2). (3) Where the uncontroverted allegations made in the FIR or complaint and the evidence collected in support of the same do not disclose the commission of any offence and make out a case against the accused.'”

The Court also cited Pepsi Foods Ltd. vs. Special Judicial Magistrate, which affirmed that “High Court can exercise its power of judicial review in criminal matters. In State of Haryana and Ors. v. Bhajan Lal and Ors., this Court examined the extraordinary power under Article 226 of the Constitution and also the inherent powers under Section 482 of the Code which it said could be exercised by the High Court either to prevent abuse of the process of any court or otherwise to secure the ends of justice.”

In Madhaurao Juuajirao Scindia vs. Sambhajirao Chandrajirao Angre, the Court had reasoned that “the criminal process cannot be utilized for any oblique purpose and held that while entertaining an application for quashing an FIR at the initial stage, the test to be applied is whether the uncontroverted allegations prima facie establish the offence. This Court also concluded that the court should quash those criminal cases where the chances of an ultimate conviction are bleak and no useful purpose is likely to be served by continuation of a criminal prosecution.”

The Supreme Court conducted a detailed examination of the specific legal provisions invoked against the appellants. The Court analyzed Sections 290 (punishment for public nuisance), 341 (punishment for wrongful restraint), and 171F (punishment for undue influence and personation at election) of the Indian Penal Code, along with Section 34 of the Police Act, 1861.

In its crucial finding, the Court stated: “On a combined reading of the FIR and the charge-sheet, we fail to understand as to how the allegations against the appellants herein could be brought within the scope and ambit of the aforesaid provisions. Taking the allegations in the FIR and the charge-sheet as they stand, the crucial ingredients of the offences under Sections 290, 341, 171F read with 34 IPC and Section 34 of the Police Act, 1861 are entirely absent.”

The Court elaborated: “A reading of the FIR and the charge-sheet neither discloses any act committed or illegal commission that caused common injury, danger, annoyance to the public or any section of the public or interference with their public rights, nor do they disclose any voluntary obstruction to a person that prevents them from proceeding in any direction that they have a right to proceed in. Further they do not disclose any material to suggest that there was any undue influence at elections, impersonation at elections or any act committed with the intention to interfere with the free exercise of electoral rights.”

The judgment further noted: “Further they do not suggest that any act was committed on a road or in an open place within the limits of a town that caused inconvenience, annoyance or posed a risk of danger or inquiry or damage to the public, and do not disclose any of the eight specified actions under Section 34 of the Police Act, 1861. Therefore, even if the case of the respondent-State is accepted at its face value, it cannot be concluded that the appellants, while conducting the rally and dharna, engaged in any form of obstruction of the road in a manner that led to the offences alleged.”

The Supreme Court made a significant observation about the constitutional rights involved, stating: “The appellants were exercising their right to freedom of speech and expression and to assemble peacefully. Therefore, no purpose will be served by continuing the prosecution.”

The Court criticized the High Court’s approach, noting that “The High Court erred in concluding that there were specific allegations against the appellants and that there were no tenable grounds to quash the proceedings, and therefore, proceeded to dismiss the application under Section 482 CrPC on a completely misconceived basis. It would have been appropriate for the High Court to have exercised the power available under Section 482 CrPC to prevent abuse of the court’s process.”

In its final ruling, the Supreme Court allowed the appeals and set aside the High Court’s judgment. The Court quashed FIR No. 102 of 2019 and all subsequent proceedings in C.C. No. 1015 of 2021, bringing an end to the six-year legal battle that had hung over the educationists.

This judgment serves as an important precedent protecting citizens’ rights to peaceful protest and assembly, particularly during electoral periods when authorities often invoke stringent measures to maintain order. The Supreme Court’s careful analysis demonstrates that while reasonable restrictions on fundamental rights are permissible, criminal prosecution cannot be used as a tool to suppress legitimate democratic expression. The ruling reinforces that peaceful protests, even when conducted without prior permission during election periods, do not automatically constitute criminal offenses unless they involve genuine public nuisance, obstruction, or electoral malpractice as defined by law.

The decision also underscores the judiciary’s role as protector of constitutional rights and its willingness to intervene when criminal processes are misused against citizens exercising their democratic freedoms. By quashing the proceedings, the Supreme Court has sent a clear message that the right to protest peacefully remains a cornerstone of Indian democracy, subject only to reasonable restrictions that must be precisely defined and properly applied.

Petitioner Name: Manchu Mohan Babu, Manchu Vishnu Vardhan Babu.Respondent Name: State of Andhra Pradesh & Another.Judgment By: Justice B. V. Nagarathna, Justice K.V. Viswanathan.Place Of Incident: Tirupati.Judgment Date: 31-07-2025.Result: allowed.

Don’t miss out on the full details! Download the complete judgment in PDF format below and gain valuable insights instantly!

Download Judgment: manchu-mohan-babu,-m-vs-state-of-andhra-prad-supreme-court-of-india-judgment-dated-31-07-2025.pdf

Directly Download Judgment: Directly download this Judgment

See all petitions in Bail and Anticipatory Bail

See all petitions in Fraud and Forgery

See all petitions in Custodial Deaths and Police Misconduct

See all petitions in Public Interest Litigation

See all petitions in Fundamental Rights

See all petitions in Judgment by B.V. Nagarathna

See all petitions in Judgment by K.V. Viswanathan

See all petitions in allowed

See all petitions in Quashed

See all petitions in supreme court of India judgments July 2025

See all petitions in 2025 judgments

See all posts in Criminal Cases Category

See all allowed petitions in Criminal Cases Category

See all Dismissed petitions in Criminal Cases Category

See all partially allowed petitions in Criminal Cases Category