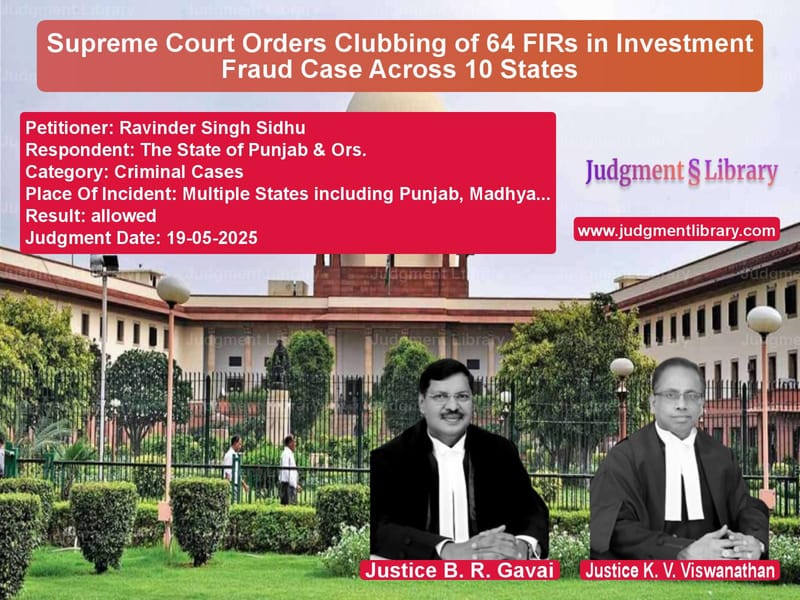

Supreme Court Orders Clubbing of 64 FIRs in Investment Fraud Case Across 10 States

In a landmark judgment that addresses the complex issue of multiple criminal proceedings across different states, the Supreme Court of India has delivered a significant verdict in the case of Ravinder Singh Sidhu, who faced 64 separate FIRs across 10 states for alleged financial fraud. The petitioner, who has been in custody since October 2018, sought relief from the overwhelming legal burden of defending himself in numerous courts spread across the country. What began as a petition seeking transfer of all cases to a single court in Panchkula, Haryana, ultimately transformed into a practical solution that balances the interests of justice with the procedural realities of our federal system.

The case revolves around Ravinder Singh Sidhu, former Managing Director of KIM Infrastructure and Developers Limited (KIDL), who along with other directors is alleged to have floated investment schemes promising high returns to investors. The company offered two primary schemes – a lumpsum payment plan and a deferred payment plan – where customers were allegedly lured with promises of developed land allocations. When the company failed to honor its commitments and defaulted on repayments, investors across multiple states began filing complaints, leading to the registration of 64 FIRs in Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Gujarat, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Himachal Pradesh.

The legal journey of this case dates back to 2010 when Writ Petition No. 3332 of 2010 was filed before the Madhya Pradesh High Court seeking inquiry against financial companies including KIDL. The High Court ordered an investigation by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which conducted a preliminary inquiry and submitted a report concluding that many of the named companies indulged in profiteering schemes without having the capacity to repay investors along with the promised returns. The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) also initiated inquiries against KIDL, rejecting the company’s attempt to get its scheme registered as a Collective Investment Scheme (CIS) under the SEBI Act, 1992.

During the proceedings before the Supreme Court, the petitioner’s senior counsel made a significant concession, stating that he would only press for consolidation of multiple FIRs in each state to one district within the respective states, rather than seeking transfer of all cases to a single court in Haryana. This pragmatic approach found acceptance among the responding states, which had initially opposed clubbing but eventually reached a broad consensus about consolidating cases within their respective jurisdictions.

The Supreme Court, in its judgment delivered by Justice K.V. Viswanathan, emphasized the importance of avoiding multiplicity of proceedings, stating that “multiplicity of proceedings will not be in larger public interest.” The Court further observed that “since many States have invoked local Acts, particularly the Act dealing with the Protection of Interest of Depositors, transferring them out of the State also will not serve the ends of justice.” This recognition of the federal structure and the applicability of state-specific laws became the cornerstone of the Court’s approach to the problem.

The Court drew upon established legal principles from previous judgments, particularly Radhey Shyam v. State of Haryana and Ors. (2022) and Abhishek Singh Chauhan v. Union of India and Ors. (2022), which had addressed similar issues of multiple FIRs. Following this precedent, the Court directed that the correct course of action would be to merge the FIRs with the earliest FIR in each concerned state.

In its detailed order, the Supreme Court provided specific directions for each state, identifying the principal FIR in each jurisdiction with which all other FIRs in that state would be merged. The Court clarified that “if the first FIR in the respective States is registered in respect of offence under the general law and not the special enactment, but if the subsequent FIRs now clubbed are registered in connection with the special law or registered also in connection with the special law, the same after clubbing must be tried under the special law by the Special Court(s).”

Read also: https://judgmentlibrary.com/supreme-court-cancels-bail-in-murder-case-land-dispute-turns-deadly/

The consolidation plan outlined by the Court is comprehensive and state-specific. In Gujarat, three FIRs will be merged with FIR No. I-79/2018 dated September 27, 2018, registered at Bhavnagar Gangajaliya police station. In Haryana, five FIRs will be consolidated with FIR No. 24/2018 dated January 16, 2018, from Ambala Cant police station. Himachal Pradesh’s single additional FIR will merge with FIR No. 13/2019 from Sujanpur Tira police station. Madhya Pradesh’s additional case will combine with FIR No. 496/2018 dated December 5, 2018, from Jabalpur’s Lordganj police station.

Punjab, which had the highest number of FIRs at 23, will see 16 of them merged with FIR No. 198/2018 dated October 23, 2018, from SAS Nagar’s Phase I police station. Rajasthan’s three additional FIRs will consolidate with FIR No. 878/2018 dated November 20, 2018, from Karauli’s Hindon police station. Uttar Pradesh’s 14 FIRs will merge with FIR No. 28/2019 dated January 13, 2019, from Basti’s Kotwali police station. Uttarakhand’s four FIRs will combine with FIR No. 107/2018 dated October 30, 2018, from Pithoragarh’s Kotwali police station. For Chhattisgarh and Delhi, which have only one case each, the question of clubbing doesn’t arise.

The Court provided crucial procedural clarifications, directing that while the first FIR would be treated as the principal FIR, “the subsequent FIRs in each State shall be treated as Statements under Section 161 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973.” The investigating officer in the criminal case arising from the principal FIR would be free to file supplementary charge-sheets after collating all records concerning other FIRs clubbed under this order.

In a significant relief to the petitioner, the Court addressed the bail aspect, stating that “in case the petitioner has been granted bail in connection with the principal proceeding/criminal case to which the other cases have been clubbed, the bail so granted must enure to the petitioner’s favour in the other FIRs now clubbed as well.” However, the Court added an important caveat: if the principal FIR is limited to offences under general law but subsequent FIRs contain allegations attracting offences under special enactments, the Special Court would be entitled to insist on a fresh bail application for those specific offences.

The offenses involved in these cases primarily include Sections 406 (criminal breach of trust), 420 (cheating), 465 (forgery), 467 (forgery of valuable security), 468 (forgery for purpose of cheating), 471 (using as genuine a forged document) read with Section 120B (criminal conspiracy), 34 (common intention), 263 (fraudulent use of false instrument for weighing), and 114 (abettor present when offence committed) of the Indian Penal Code. Additionally, various state-specific laws have been invoked, including the Gujarat Police Act, 1951; the Haryana Protection of Interest of Depositors in Financial Establishment Act, 2013; the Prize Chits And Money Circulation Schemes (Banning) Act, 1978; the Madhya Pradesh Nikshepakon Ke Hiton Ka Sanrakshan Adhiniyam, 2000; and the Uttarakhand Protection of Interests of Depositors (in Financial Establishments) Act, 2005.

The current status of these cases varies significantly. According to the Court’s records, trials have concluded in some cases with three convictions recorded. Two cases have resulted in acquittals, two cases have cancellation reports filed, 15 cases are at the evidence stage, and 21 cases are at the stage where charge-sheets have been filed. The Court specifically noted that it was not concerned with cases where convictions, acquittals, or cancellation reports have already been finalized.

This judgment represents a significant development in the Indian criminal justice system’s approach to multi-state litigation. By ordering state-wise consolidation rather than complete centralization, the Court has struck a balance between the practical difficulties faced by an accused in defending multiple cases and the legitimate interests of different states in prosecuting offenses committed within their territories under their specific laws.

The Supreme Court exercised its powers under Article 32 read with Article 142 of the Constitution of India to pass this order, emphasizing the unique circumstances of the case and the need to ensure that the ends of justice are served. The judgment acknowledges the practical realities of our federal system while providing relief against the oppressive burden of defending numerous similar cases across different jurisdictions.

This case highlights the growing challenge of multi-jurisdictional financial crimes in India and the need for a coherent legal framework to address them. The Supreme Court’s pragmatic approach in this matter sets an important precedent for handling similar cases in the future, where technological advancements and interstate business operations increasingly lead to legal proceedings spanning multiple states.

The judgment also underscores the importance of judicial innovation in addressing complex procedural challenges. By treating subsequent FIRs as statements under Section 161 CrPC rather than maintaining them as separate cases, the Court has created a mechanism that preserves all evidence and allegations while eliminating the procedural nightmare of coordinating dozens of separate trials.

As the investigating agencies now begin the process of consolidating these cases according to the Supreme Court’s directions, this judgment will likely be studied and cited in numerous future cases involving multi-state litigation. It represents a significant step toward modernizing India’s criminal justice system to handle the complexities of 21st-century crimes while protecting the fundamental rights of accused persons against procedural oppression.

The successful implementation of this consolidation order will depend on coordination between various state police forces, prosecuting agencies, and judicial authorities. However, the clarity and specificity of the Supreme Court’s directions provide a solid framework for this coordination to occur, potentially setting a template for similar multi-jurisdictional cases in the future.

Petitioner Name: Ravinder Singh Sidhu.Respondent Name: The State of Punjab & Ors..Judgment By: Justice B. R. Gavai, Justice K. V. Viswanathan.Place Of Incident: Multiple States including Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Gujarat, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh.Judgment Date: 19-05-2025.Result: allowed.

Don’t miss out on the full details! Download the complete judgment in PDF format below and gain valuable insights instantly!

Download Judgment: ravinder-singh-sidhu-vs-the-state-of-punjab-supreme-court-of-india-judgment-dated-19-05-2025.pdf

Directly Download Judgment: Directly download this Judgment

See all petitions in Fraud and Forgery

See all petitions in Bail and Anticipatory Bail

See all petitions in Money Laundering Cases

See all petitions in Extortion and Blackmail

See all petitions in Other Cases

See all petitions in Judgment by B R Gavai

See all petitions in Judgment by K.V. Viswanathan

See all petitions in allowed

See all petitions in supreme court of India judgments May 2025

See all petitions in 2025 judgments

See all posts in Criminal Cases Category

See all allowed petitions in Criminal Cases Category

See all Dismissed petitions in Criminal Cases Category

See all partially allowed petitions in Criminal Cases Category