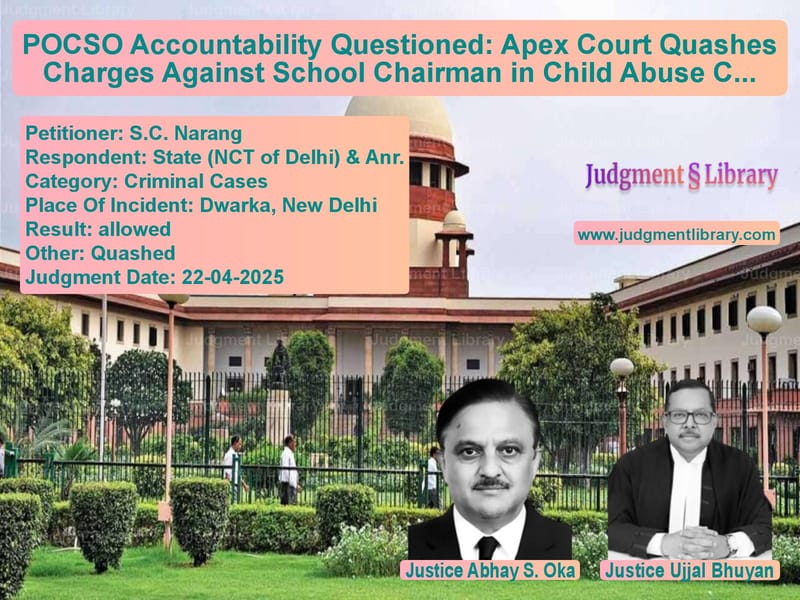

POCSO Accountability Questioned: Apex Court Quashes Charges Against School Chairman in Child Abuse Case

The harrowing tale of a four-year-old girl’s alleged sexual assault inside a school in Dwarka, New Delhi, brought the nation’s attention to the issue of safety and accountability in educational institutions. The matter eventually reached the highest court of the country, where the Supreme Court deliberated not only the gravity of the incident but also the limits of legal responsibility under the Juvenile Justice Act (JJ Act) and the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO). At the heart of the case was whether S.C. Narang, the Chairman of the school’s Managing Committee, could be held criminally liable under Section 75 of the JJ Act despite not having direct control over the child.

The Incident and Initial Proceedings

On November 17, 2017, a four-year-old nursery student at Maxfort School, Dwarka, complained of pain in her private parts. Her mother, shocked by the details provided by the child, approached the authorities. An FIR was promptly filed under Section 376 of the Indian Penal Code and Section 21 of the POCSO Act. Upon investigation, however, the police concluded that the prime accused was a classmate under the age of seven, thereby making him immune to criminal prosecution. Nonetheless, a charge sheet was filed against the school authorities—specifically, the Principal, two teachers, and the Vice-Chairman—for negligence under Section 21 of the POCSO Act read with Section 75 of the JJ Act.

The mother of the victim, unsatisfied with the exclusion of the Chairman from the list of accused, filed two protest petitions. The second petition led the Special Judge to issue a summons to the Chairman, Mr. S.C. Narang. This decision was challenged by the appellant through a revision petition in the High Court, which was dismissed. Consequently, the matter escalated to the Supreme Court.

Arguments Presented

During the hearing, the learned senior counsel for the appellant emphasized that the charge sheet did not and could not logically apply Section 75 of the JJ Act to the appellant. He argued:

“Even taking the case of the prosecution as correct, it cannot be said that the appellant had the actual charge or control over the victim child.”

He explained that although the Directorate of Education had issued guidelines on September 15, 2017, requiring the installation of CCTV cameras in all critical areas of schools, the alleged incident occurred merely a few days later. Hence, implementation was still underway. Moreover, he pointed out that the school Principal, two teachers, and the Vice-Chairman were already facing prosecution under Section 75 of the JJ Act, questioning the need to summon the Chairman who had no direct operational involvement.

On the other hand, the Additional Solicitor General for the State, and the counsel for the second respondent (the victim’s mother), contended that:

“As the Chairman of the institution running the school, the appellant is fully responsible for taking care of the children enrolled in the school.”

They maintained that moral and managerial responsibility fell squarely on the Chairman, and therefore, his inclusion under Section 75 was justified.

Supreme Court’s Observations and Reasoning

Justice Abhay S. Oka, delivering the judgment, focused on a precise interpretation of Section 75 of the JJ Act, which states:

“Whoever, having the actual charge of, or control over, a child, assaults, abandons, abuses, exposes or willfully neglects the child … shall be punishable …”

He clarified that the reference to ‘child’ in this context referred specifically to the victim of the offence. He stated unequivocally:

“It is impossible to even allege that the appellant, being Chairman of the Managing Committee, had the actual charge of all the children studying in the school … He may have control over the management of the institution which runs the School. That does not give him control over every child studying in the school.”

In the court’s view, managerial authority does not automatically imply physical or custodial control over children. Moral responsibility, while important, does not equate to legal culpability under Section 75.

Justice Oka further observed:

“Assuming that the appellant was morally responsible, Section 75 of the JJ Act cannot be applied unless it is shown that the appellant had the actual charge of the victim child or control over the victim child.”

Final Verdict

After thoroughly reviewing the facts, arguments, and applicable legal provisions, the Supreme Court concluded that no case was made out against the Chairman. The apex court accordingly quashed the impugned orders of both the Special Court and the High Court:

Read also: https://judgmentlibrary.com/supreme-court-clarifies-probation-rules-in-cruelty-case-key-takeaways/

“By no stretch of imagination, Section 75 of the JJ Act could have been applied against the appellant.”

The bench, comprising Justices Abhay S. Oka and Ujjal Bhuyan, allowed the appeal and made it explicitly clear that their findings were specific to the appellant’s case and should not influence the pending trial against the other accused.

“What is held in this order will have no bearing on the pending case before the Special Court, and all questions in that regard are left open.”

Conclusion

The judgment establishes a crucial precedent in distinguishing between moral accountability and legal responsibility in the administration of educational institutions. While the emotional gravity of the incident remains undisputed, the court’s focus remained anchored on legal interpretation and principles of justice. The decision draws a clear line between managerial oversight and personal liability, ensuring that criminal laws are applied only where legally and factually sustainable. For school administrators, it is both a reminder and a relief: accountability mechanisms must be implemented earnestly, but legal liability requires demonstrable personal involvement or negligence under the statute.

Petitioner Name: S.C. Narang.Respondent Name: State (NCT of Delhi) & Anr..Judgment By: Justice Abhay S. Oka, Justice Ujjal Bhuyan.Place Of Incident: Dwarka, New Delhi.Judgment Date: 22-04-2025.Result: allowed.

Don’t miss out on the full details! Download the complete judgment in PDF format below and gain valuable insights instantly!

Download Judgment: s.c.-narang-vs-state-(nct-of-delhi)-supreme-court-of-india-judgment-dated-22-04-2025.pdf

Directly Download Judgment: Directly download this Judgment

See all petitions in Bail and Anticipatory Bail

See all petitions in Other Cases

See all petitions in Judgment by Abhay S. Oka

See all petitions in Judgment by Ujjal Bhuyan

See all petitions in allowed

See all petitions in Quashed

See all petitions in supreme court of India judgments April 2025

See all petitions in 2025 judgments

See all posts in Criminal Cases Category

See all allowed petitions in Criminal Cases Category

See all Dismissed petitions in Criminal Cases Category

See all partially allowed petitions in Criminal Cases Category