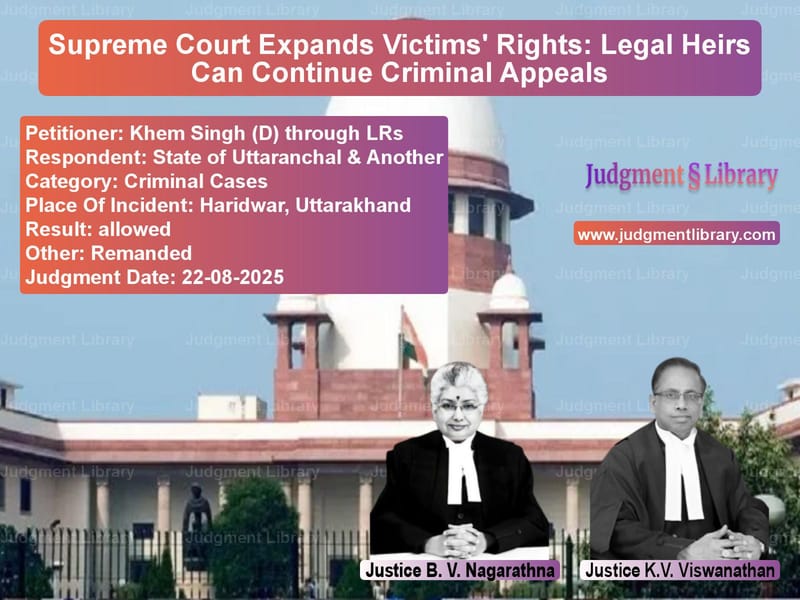

Supreme Court Expands Victims’ Rights: Legal Heirs Can Continue Criminal Appeals

In a landmark judgment that significantly expands the rights of crime victims in India’s criminal justice system, the Supreme Court has delivered a verdict that ensures justice doesn’t end with the death of a victim during legal proceedings. The case involved a tragic incident dating back to 1992 where a family became victims of a violent attack resulting in one death and multiple injuries. The legal journey that followed over three decades reveals much about the evolution of victims’ rights in Indian criminal jurisprudence and the ongoing struggle to balance the scales of justice between the accused and those who suffer from criminal acts.

The case originated from a violent incident on December 9, 1992, in Haridwar, Uttarakhand, where longstanding enmity between two groups escalated into a deadly confrontation. According to the prosecution, informant Tara Chand, his brother Virendra Singh, and his son Khem Singh were attacked by multiple accused using guns, sharp weapons, and bricks. The attack proved fatal for Virendra Singh, while Tara Chand and Khem Singh sustained serious injuries. The Sessions Court convicted three accused – Ashok, Pramod, and Anil @ Neelu – sentencing them to life imprisonment for murder and additional punishments for other offenses. However, the Uttarakhand High Court later acquitted these accused through a judgment that would become the subject of extensive legal scrutiny.

The Legal Battle Over Substitution

When the original appellant Khem Singh died during the pendency of his appeal before the Supreme Court, his son Raj Kumar filed applications seeking substitution to continue the legal battle. This raised a fundamental question about victims’ rights in criminal appeals – could legal heirs continue an appeal when the original victim-appellant dies during proceedings?

The applicant’s counsel made a compelling case, arguing that “the proviso to Section 372 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 which has the expression ‘the right to prefer an appeal’ would also include ‘the right to prosecute an appeal’.” He emphasized that “the right to prosecute an appeal given to a legal heir of the victim must also be construed to extend to a case where the legal heir of the original appellant, who was also an injured victim in the instant case must be brought on record.”

The respondents’ counsel vehemently opposed the substitution, contending that “although the said provision refers to an appeal filed against a conviction, sub-section (1) of Section 394 CrPC deals with abatement of an appeal on the death of an accused when the appeal was filed under Sections 377 or 378 CrPC.” They argued that “the expression ‘near relative’ in the proviso to sub-section (2) of Section 394 CrPC is of a wider connotation to include a parent, spouse, lineal descendant, brother or sister, but such an expression cannot be applied in the case of substitution of an original victim who had preferred an appeal on his demise during the pendency of his appeal.”

The Supreme Court’s Expansive Interpretation

The Supreme Court bench comprising Justices B.V. Nagarathna and K.V. Viswanathan delivered a comprehensive judgment that extensively analyzed the evolution of victims’ rights in Indian criminal law. The Court traced the legislative history from the 154th Report of the Law Commission of India in 1996 through the Justice Malimath Committee Report of 2003, which specifically recommended that “the victim shall have a right to prefer an appeal against any adverse order passed by the court acquitting the accused, convicting for a lesser offence, imposing inadequate sentence, or granting inadequate compensation.”

The Court made several crucial observations about the nature of victims’ rights, noting that “the expression ‘victim’ is initially exhaustive and thereafter inclusive. The expression ‘victim’ means a person who has suffered any loss or injury. The loss or injury could be either physical, mental, a financial loss or injury.” The Court emphasized that “the expressions ‘loss’ or ‘injury’ themselves are of a very broad import which expressions also enlarge the scope of the expression ‘victim’.”

In a significant interpretation, the Court held that “the expression ‘the right to prefer an appeal’ in the proviso to Section 372 CrPC cannot be limited to mean ‘only the filing of an appeal’. Mere filing of an appeal in the absence of prosecution of an appeal is of no avail.” The Court reasoned that “we interpret the expression ‘the right to prefer an appeal’ to also include the ‘right to prosecute an appeal’.”

Balancing Rights and Ensuring Justice

The Court drew an important parallel between the rights of accused persons and victims, observing that “the right to prefer an appeal is no doubt a statutory right and such a right in an accused against a conviction is not merely a statutory right but can also be construed to be a fundamental right under Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. If that is so, then the right of a victim of an offence to prefer an appeal cannot be equated with the right of the State or the complainant to prefer an appeal unless the victim is also the complainant.”

The Court emphasized the importance of giving full effect to legislative intent, stating that “any curtailing of the legal right to prosecute an appeal on the death of an original appellant by his legal heir would make the proviso to Section 372 CrPC wholly redundant and in fact may result in a situation which is contrary to the entire object with which the Parliament had inserted the proviso to Section 372 CrPC.”

In a powerful statement about access to justice, the Court referenced its earlier Constitution Bench judgment in PSR Sadhanantham vs. Arunachalam, noting that “the strictest vigilance over abuse of the process of the Court is necessary, as ordinarily meddlesome bystanders should not be granted a ‘visa’, but access to justice to every bona fide seeker is a democratic dimension of remedial jurisprudence.”

The Remand for Proper Adjudication

After allowing the substitution application, the Court turned to the merits of the criminal appeals. The appellant’s counsel made a two-fold submission, first contending that “even without going into the merits of the case, the manner and tenor of the judgment may be considered; that this is a judgment of a High Court which was considering a first appeal against a judgment and order of conviction which appeals were filed by respondents – accused; that in a cryptic manner, the judgment has been delivered by the High Court acquitting the respondents – accused.”

The respondents’ counsel countered that “the High Court may have given the judgment pithily but it is not without substance. Merely because the impugned judgment is short and not lengthy cannot make it an erroneous judgment so long as the reasoning is evident and there is a basis for the findings arrived at.”

The Court sided with the appellant, emphasizing that “while hearing the appeals under Section 374(2) of the CrPC, the High Court is exercising its appellate jurisdiction. There shall be independent application of mind in deciding the criminal appeal against conviction. It is the duty of an appellate court to independently evaluate the evidence presented and determine whether such evidence is credible.” The Court further elaborated that “as the first appellate court, the High Court is expected to evaluate the evidence including the medical evidence, statement of the victim, statements of the witnesses and the defence version with due care.”

Broader Implications for Criminal Justice

This judgment represents a significant advancement in victims’ rights within India’s criminal justice system. By interpreting the ‘right to prefer an appeal’ to include the ‘right to prosecute an appeal,’ the Supreme Court has ensured that justice for victims doesn’t become infructuous due to their death during legal proceedings. The Court’s recognition that victims’ rights should be on par with those of accused persons marks a important shift toward a more balanced criminal justice system.

The Court’s decision to remand the matter to the High Court for fresh consideration, citing the cryptic nature of the earlier judgment, reinforces the importance of reasoned decisions in criminal appeals, particularly when personal liberty is at stake. The Court’s observation that “while the judgment need not be excessively lengthy, it must reflect a proper application of mind to crucial evidence” serves as an important reminder to appellate courts about their responsibilities in criminal matters.

This judgment strengthens the position of victims in the criminal justice process, ensuring that their quest for justice can continue through their legal heirs when unfortunate circumstances prevent them from seeing the legal process through to its conclusion. It represents a significant step toward realizing the constitutional vision of equal justice for all, balancing the rights of accused persons with the legitimate interests of victims in the criminal justice process.

Petitioner Name: Khem Singh (D) through LRs.Respondent Name: State of Uttaranchal & Another.Judgment By: Justice B. V. Nagarathna, Justice K.V. Viswanathan.Place Of Incident: Haridwar, Uttarakhand.Judgment Date: 22-08-2025.Result: allowed.

Don’t miss out on the full details! Download the complete judgment in PDF format below and gain valuable insights instantly!

Download Judgment: khem-singh-(d)-throu-vs-state-of-uttaranchal-supreme-court-of-india-judgment-dated-22-08-2025.pdf

Directly Download Judgment: Directly download this Judgment

See all petitions in Murder Cases

See all petitions in Bail and Anticipatory Bail

See all petitions in Attempt to Murder Cases

See all petitions in Judgment by B.V. Nagarathna

See all petitions in Judgment by K.V. Viswanathan

See all petitions in allowed

See all petitions in Remanded

See all petitions in supreme court of India judgments August 2025

See all petitions in 2025 judgments

See all posts in Criminal Cases Category

See all allowed petitions in Criminal Cases Category

See all Dismissed petitions in Criminal Cases Category

See all partially allowed petitions in Criminal Cases Category