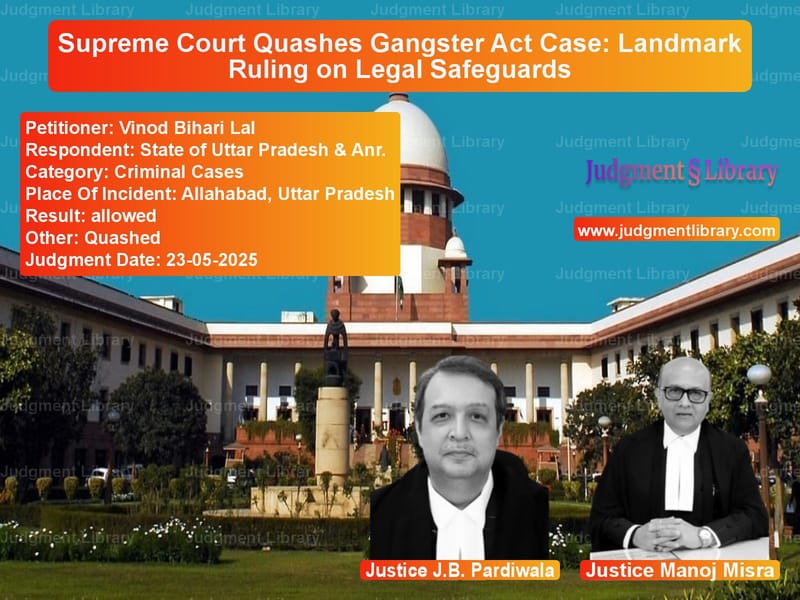

Supreme Court Quashes Gangster Act Case: Landmark Ruling on Legal Safeguards

In a significant judgment that reinforces the importance of procedural safeguards in criminal law, the Supreme Court of India delivered a landmark ruling on May 23, 2025, quashing criminal proceedings under the Uttar Pradesh Gangsters and Anti-Social Activities (Prevention) Act, 1986 against appellant Vinod Bihari Lal. The case, which involved serious allegations of organized criminal activity, ultimately revealed critical flaws in the investigation and approval process that led the Court to conclude that continuing the prosecution would amount to an abuse of the legal process. The judgment, authored by Justice J.B. Pardiwala with Justice Manoj Misra concurring, provides crucial guidance on the proper application of anti-gang legislation and the constitutional protections available to citizens against arbitrary state action.

The legal battle began when Vinod Bihari Lal found himself facing charges under the stringent Gangster Act based on multiple First Information Reports (FIRs) alleging various economic offenses and criminal activities. The case traveled through the lower courts until reaching the Supreme Court, where the appellant challenged both the criminal proceedings and the non-bailable warrants issued against him. What emerged from the Court’s detailed examination was a troubling pattern of procedural irregularities, non-compliance with statutory requirements, and a fundamental failure to establish the essential elements required to invoke the draconian provisions of the Gangster Act.

The Factual Background

The case originated from FIR No. 850 of 2018 registered at P.S. Naini, District Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh, under Sections 2 and 3 of the UP Gangsters and Anti-Social Activities (Prevention) Act, 1986. The FIR alleged that the appellant, along with one David Dutta, constituted an organized gang involved in economic offenses, fraud, and cheating. The prosecution’s case relied on five base FIRs registered between 2017 and 2018, which formed the foundation for invoking the Gangster Act.

Read also: https://judgmentlibrary.com/cbi-cotton-msp-fraud-case-supreme-court-sets-aside-discharge-of-accused/

The base FIRs included allegations ranging from forgery of documents and embezzlement of student fees to more serious charges under Sections 307 (attempt to murder) and 506 (criminal intimidation) of the Indian Penal Code. However, as the Supreme Court would later note, several of these base cases had already been stayed by higher courts, and one had been quashed entirely by the Supreme Court itself in separate proceedings.

The gang-chart purportedly approved by the District Magistrate, Allahabad on July 28, 2018, became the centerpiece of the prosecution’s case. This document, which listed the appellant’s alleged criminal activities, was supposed to demonstrate the systematic and organized nature of his operations, thereby justifying the application of the special legislation meant to combat gang-related crimes.

Arguments Presented by the Appellant

Mr. Siddhartha Dave, the learned Senior Counsel appearing for the appellant, presented a multi-pronged challenge to the proceedings. He argued that “the four base FIRs, namely FIR No. 170/2017, FIR No. 726/2017, FIR No. 761/2017 and FIR No. 244/2017 respectively, do not attribute any specific overt act to the appellant except for the omnibus allegation that he, in collusion with the other accused persons, forged documents for the purpose of grabbing land and embezzled money from the fees deposited by the students.”

On the crucial issue of what constitutes a “gang” under the Act, Mr. Dave contended that “a plain reading of Section 2(b) of the Act of 1986 reveals that a group of persons can be regarded a ‘gang’ only if they engage in any anti-social activities through violence, or threat, or show of violence, or intimidation, or coercion with the object of disturbing public order and gaining any undue temporal, or pecuniary, material or other advantage for himself.”

The appellant’s counsel also highlighted serious procedural irregularities, noting that “the appellant is alleged to be running a ‘gang’ with one David Dutta, who is also named as an accused in the base FIR No. 170/2017. However, the other accused persons named in the remaining FIRs have not been arrayed as accused in the subject FIR, which has been registered under the Act of 1986. In other words, there is no plausible explanation as to why those other accused persons were not included in the subject FIR, if the same is based on the allegations contained in the base FIR.”

Arguments Presented by the Respondents

Ms. Garima Prashad, the learned Additional Advocate General appearing for the respondent-State, defended the proceedings and argued that the High Court had committed no error in refusing to quash the case. She submitted that “the subject FIR contains allegations that the appellant resorted to public threats and coercion, including physical violence, which squarely falls within the ambit of anti-social activities as defined Section 2(b) of the Act of 1986.”

The State’s counsel further emphasized the appellant’s criminal antecedents, pointing out that “there are thirty-two criminal cases pending against the appellant, in which chargesheets have been filed, disclosing serious allegations against him.” She argued that these demonstrated a pattern of criminal behavior that justified the invocation of the Gangster Act.

The Supreme Court’s Legal Analysis

The Supreme Court began its analysis by examining the definition of “gang” under Section 2(b) of the 1986 Act, which states: “‘Gang’ means a group of persons, who acting either singly or collectively, by violence, or threat or show of violence, or intimidation, or coercion or otherwise with the object of disturbing public order or of gaining any undue temporal, pecuniary, material or other advantage for himself or any other person, indulge in anti-social activities.”

The Court identified four essential elements required to establish the existence of a gang: “i. A group of persons i.e., there can be no gang of one person; ii. The group of persons, acting either individually or collectively, indulges in anti-social activities as enumerated in clauses (i) to (xxv) of Section 2(b); iii. Indulgence in such anti-social activities is by means of violence, or threat, or show of violence, or intimidation, or coercion, or otherwise; iv. Use of such means is with the object of disturbing public order, or gaining any undue temporal, pecuniary, material or other advantage for himself or any other person.”

The Court emphasized that “the definition of the term ‘gang’ is not attracted by mere association with a miscreant group. For such a group to metamorphize into a gang, it must engage in anti-social activities enumerated in clauses (i) to (xxv) of Section 2(b), and these must be committed for the object mentioned thereunder.”

Examination of the Base FIRs

The Court conducted a detailed examination of the five base FIRs that formed the foundation of the Gangster Act case. It found that “in the three base FIRs – FIR No. 726/2017, FIR No. 761/2017, and FIR No. 244/2017, respectively, the allegations against the appellant pertain to offences under Chapters 16, 17 and 22 of the IPC and thus, may fall within the scope of anti-social activities itemized under Section 2(b). Even assuming, for the sake of argument, that these acts were committed by any of the means specified therein, they do not, even in the remotest possibility, appear to us that they had been committed with the object of disturbing public order or to gain any undue temporal, pecuniary, material or other advantage for himself or any other person.”

The Court also noted a fundamental inconsistency in the prosecution’s theory: “It is also pertinent to note that in the impugned proceedings, the appellant and one David Dutta have been arraigned as gangsters, whereas in the above-mentioned three base FIRs, David Dutta does not figure at all as an accused. In such circumstances, the gang-chart could not have listed the said three FIRs, as the base FIRs, against the appellant and David Dutta together.”

Procedural Irregularities and Non-Compliance with Rules

The Court found multiple violations of the Uttar Pradesh Gangster and Anti-Social Activities (Prevention) Rules, 2021, which establish mandatory procedures for invoking the Act. Rule 5(3)(a) requires that “a gang chart shall be approved only after due discussion in a joint meeting comprising the District Magistrate, Commissioner of Police, Senior Superintendent of Police, Superintendent of Police, and not through a summary process.”

The Court observed that “there is nothing on record, even upon a microscopic examination, to indicate that a joint meeting was held prior to approval of the gang-chart. It is apparent that the gang-chart was approved summarily, without any discussion. It was forwarded and approved swiftly, without regard for compliance with the relevant rules.”

Rule 17 specifically prohibits the use of pre-printed gang-charts, mandating that “the Competent Authority shall be bound to exercise its own independent mind while forwarding the gang-chart. A pre-printed rubber seal gang-chart should not be signed by the Competent Authority; otherwise the same shall tantamount to the fact that the Competent Authority has not exercised its free mind.”

The Court found that “upon perusal of the material on record, more particularly the gang-chart, it is abundantly clear that the said gang-chart was approved by the competent authority merely by affixing his signature on a pre-printed gang-chart, an act that reflects nothing short of a complete non-application of mind and constitutes a violation of Rules 16 and 17 of the Rules of 2021 respectively.”

Principles of Quashing Criminal Proceedings

The Court reiterated the well-established principles governing the quashing of criminal proceedings, referring to the landmark case of State of Haryana v. Bhajan Lal (1992). It emphasized that courts have the power to quash proceedings “where the allegations made in the first information report or the complaint, even if they are taken at their face value and accepted in their entirety do not prima facie constitute any offence or make out a case against the accused” and “where a criminal proceeding is manifestly attended with mala fide and/or where the proceeding is maliciously instituted with an ulterior motive for wreaking vengeance on the accused and with a view to spite him due to private and personal grudge.”

The Court made an important observation about the role of criminal antecedents in quashing petitions: “However, when it comes to quashing of the FIR or criminal proceedings, the criminal antecedents of the accused cannot be the sole consideration to decline to quash the criminal proceedings. An accused has a legitimate right to say before the Court that houseover bad his antecedents may be, still if the FIR fails to disclose commission of any offence or his case falls within one of the parameters as laid down by this Court in the case of Bhajan Lal (supra), then the Court should not decline to quash the criminal case only on the ground that the accused is a history sheeter.”

The Court’s Strong Observations on Investigation

The Supreme Court expressed strong disapproval of the investigating agency’s approach, noting that “the contents of the chargesheet reflect a casual and cavalier attitude on the part of the investigating agency, as it discloses nothing beyond what was already stated in the subject FIR. Further, it remains obscure how the investigating authorities could assert that the offence under Section(s) 2 and 3 respectively stands ‘proved’ against the appellant sans enclosing any documentary proved. We strongly disapprove of this practice and cast it into the cold storage wherein the investigating authority proclaims an offence to be ‘proved’. We would like to remind that the role of investigating agencies is strictly circumscribed to conducting an impartial investigation into the alleged crime; the guilt or the innocence of the accused is for the trial court to determine.”

The Court also criticized the selective targeting in the investigation: “We find merit in the submission advanced by Mr. Dave that if the subject FIR and the gang-chart were indeed prepared on the strength of the base FIRs, there is no good or plausible explanation coming from the investigating agency as to why no investigation was initiated against other similarly placed accused persons named therein. This selective approach raises serious doubts about the bona fides of the investigating agency and integrity of the investigation undertaken under the Act of 1986.”

Conclusion and Directions

After a comprehensive analysis of the facts and law, the Supreme Court concluded that “the continuation of Special Sessions Trial No. 54 of 2019 arising out of FIR No. 850 of 2018 registered at P.S. Naini, District Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh will be nothing but abuse of the process of the law.”

The Court allowed the appeals and quashed all proceedings arising from the FIR. It also set aside the non-bailable warrants issued against the appellant. However, the Court clarified that “the observations made in this judgment are relevant only for the purpose of the subject FIR in question and the consequential criminal proceedings. None of the observations shall have any bearing on any of the pending criminal prosecutions or any other proceedings.”

The judgment serves as an important reminder of the constitutional safeguards available to citizens and the judiciary’s role in preventing the misuse of draconian legislation. It reinforces the principle that procedural compliance is not merely a technicality but a fundamental aspect of due process that protects individuals from arbitrary state action. The Court’s detailed examination of the Gangster Act’s requirements and its insistence on strict compliance with procedural rules establishes important precedents for future cases involving special criminal legislation.

Petitioner Name: Vinod Bihari Lal.Respondent Name: State of Uttar Pradesh & Anr..Judgment By: Justice J.B. Pardiwala, Justice Manoj Misra.Place Of Incident: Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh.Judgment Date: 23-05-2025.Result: allowed.

Don’t miss out on the full details! Download the complete judgment in PDF format below and gain valuable insights instantly!

Download Judgment: vinod-bihari-lal-vs-state-of-uttar-prade-supreme-court-of-india-judgment-dated-23-05-2025.pdf

Directly Download Judgment: Directly download this Judgment

See all petitions in Bail and Anticipatory Bail

See all petitions in Cyber Crimes

See all petitions in Money Laundering Cases

See all petitions in Extortion and Blackmail

See all petitions in Attempt to Murder Cases

See all petitions in Fraud and Forgery

See all petitions in Theft and Robbery Cases

See all petitions in Custodial Deaths and Police Misconduct

See all petitions in Judgment by J.B. Pardiwala

See all petitions in Judgment by Manoj Misra

See all petitions in allowed

See all petitions in Quashed

See all petitions in supreme court of India judgments May 2025

See all petitions in 2025 judgments

See all posts in Criminal Cases Category

See all allowed petitions in Criminal Cases Category

See all Dismissed petitions in Criminal Cases Category

See all partially allowed petitions in Criminal Cases Category